IF YOU WANT TO KNOW more about Freeport’s present and past, you can’t do better than talk with John T. Mann, a surveyor, historian, author and descendantof a family that has been here for three hundred years.

John in grade school

Mann was raised just up Wolfe’s Neck Road from where his great grandfather had started a farm, and got his early education at the Grove Street School, where the town hall is now, and then Freeport High School. As the son and grandson of farmers, he was learning plenty on the side as well. When he was 17, his father, James Mann, gave him some land and advised him to build a house there, pointing out that “it takes a cage to catch a canary.” Mann followed his father’s advice and built a typical Cape Cod home where he would later live with his wife, Val, who also had historical roots including a great grandfather, Evans Cole Banks, who lived in the 18th century Pote House further down the Wolfe’s Neck Road.

Mann studied surveying at the Central Maine Vocational Technical Institute and eventually got a professional license after taking two eight hour exams. Aside from his professional skills, Mann developed the ability to uncover former uses of land that most would miss, which has proved invaluable in his work as a historian—discovering not just where the early settlers came but how they actually lived.

A historian who accompanied Mann in examining one field was struck how he read the landscape. She described Mann describing what he saw: “That’s where the barn was…. This was pasture. . . This is where the house was. . . .This is probably where the well was.” And then moving on to find remains of a possible road in the woods. Mann became particularly interested in the story of the Ulster Scots, aka the Scots Irish, who played a major role in these parts, including bringing the Manns to America in the early 18th century.

The Puritan minister in Massachusetts, Cotton Mather, had become concerned by French advances and Indian attacks in Maine and had written to clergy in Scotland and Ireland for help seeking to secure things down east. He didn’t want Catholics because they might be tied to the French, but the Scots Irish had a reputation of being tough fighters up to the task and so, despite the fact that Puritans and Ulster Scots didn’t share religious views, and given that the latter were anxious to escape the subjugation of absentee landlords, people like Gideon Mann made it to the Maine shores.

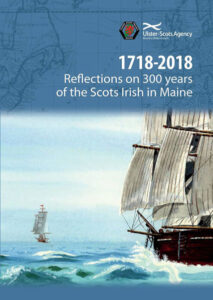

The cover of 1718-2018 Reflections on 300 years of the Scots Irish in Maine

John Mann tells the Freeport part of the story extremely well in Ulster-Scots on the Coast of Maine, Volume 1 in which he describes the Means Massacre, an Indian attack near what is now Flying Point Road in which two members of the Means family were killed and one taken captive, and which was the last of such assaults in the region. Mann also contributed to another book, 1718-2018: Reflections on 300 years of the Scots Irish in Maine. Both books are available at the Freeport Historical Society. Mann served as president of the Ulster-Scotts Project. His own family records fill seven file cabinets and a computer base storage system. As Mann notes, “The story of the Ulster-Scots, and especially their migration into, and influence on, the District of Maine, has been much overlooked and under reported.”

Lest you think of Mann as only scholarly, it is worth noting that he is also a wonderful story teller, a Maine habit that has contributed to the retention of its history. We found ourselves talking about the state’s culture such as the fact that Mainers are careful not to stick their nose into their neighbor’s business. Mann quoted his father as having told him, “You want to look after your neighbors because they’re like money in the bank. You never know when you’re going to need it.” And, he noted, “If you don’t have a sense of humor, you’re going to have trouble.”

In 1979, as Freeport got more expensive, the Manns moved to inland to Bowdoin. But John Mann remains one of the most perceptive and enjoyable voices you can hear talk about this town.